Camps and Cages: Volatile Immigration Policies Threaten New Americans’ Mental Health

More people around the world have been displaced from their homes than ever before, and the consequences are causing ripple effects in our communities. A record 70.8 million people have been forced from their homes, but fewer than half have been granted legal status as a refugees or asylum seekers. The U.S. Department of Homeland Security has slowed immigration to a trickle at the border with Mexico, infamously detaining migrants—including asylum seekers—in camps and cages. Meanwhile, the Trump Administration has capped the number of refugees entering the U.S. at 30,000 this year, leaving millions more people in ramshackle camps overseas or displaced in neighboring countries. At the height of the human migration crisis, America is welcoming the smallest number of refugees in four decades.

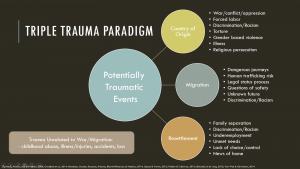

The journey to America is fraught with trauma, even for those who enter the country legally. Immigrants in flight are vulnerable to a phenomenon called the Triple Trauma Paradigm. Essentially, many immigrants are traumatized by the violence, persecution and poverty that forced them to flee their homes. Then they’re susceptible to violence, deprivation and trafficking during migration. Finally, the survivors who make it to the United States struggle with family separation, poverty and language and cultural barriers that are exacerbated by racism and xenophobia. Such experiences contribute to lasting mental health impacts, including increased rates of depression, anxiety, posttraumatic stress disorder, and substance use disorders.

We at the UNC Refugee Mental Health and Wellness Initiative are working with partner organizations to identify and support refugees who have recently arrived in the Triangle region of North Carolina. Clinical social workers and graduate-level social work students offer free home-based mental health care and coordination services, but limitations on federal funding mean we can only serve refugees in three North Carolina counties who were resettled in the U.S. fewer than five years ago. Meanwhile, America’s immigrant communities face multiple barriers to accessing mental health services, and this exacerbates existing health disparities. When left untreated, trauma can contribute to severe and persistent mental illness, chronic health conditions, underemployment, and intimate partner violence – sometimes requiring law enforcement and Child Protective Services involvement.

In the long term, expanding and shoring up a system to allow more legal migration—if not citizenship status in the U.S.—could prevent many of the traumas that refugees and asylum seekers experience after they arrive in this country. In the meantime, we at UNC Refugee Mental Health and Wellness are working with partner organizations to identify recently resettled refugees in the Triangle region of North Carolina who need help; to offer culturally appropriate treatment that addresses their needs; and to build our community’s capacity to serve refugees. We believe all people have a right to mental wellness and culturally competent care. We need your support to help our newest neighbors heal, supporting them in their journey towards finding safety and realizing their own versions of the American dream.

TERMS TO KNOW

What is status?

The legal standing of a person, as determined by a government or an international program, such as the United Nations.

Who has refugee status?

A person whom the UN has determined has been forced to flee his or her home because of war, violence or persecution. This designation is often given to ethnic groups from specific countries. More than 20 million people currently have refugee status worldwide. The United States currently resettles about 30,000 refugees per year. That’s down 60%.

Who is an asylum seeker?

A person who flees their home country, enters another country and applies for asylum. It is legal to remain in the United States while an asylum case in pending.

Who is undocumented?

A person who does not have current legal status in the country where they live. In the United States, this includes people whose legal status expired as well as those who entered the country without authorization.