It has been over a year since the COVID-19 pandemic first began to infuse grief, uncertainty, and isolation into the lives of families across the nation. Our nation’s youth are no exception to this struggle.

Adolescents, or tweens and teens, are the group of children most vulnerable to the ongoing challenges of COVID-19. Teens are in the phase of their lives where they are differentiating from their families, cultivating new and meaningful social relationships, and approaching independence. Growing up under the shadow of a global pandemic has meant that many hallmarks of typical adolescence, including connecting face-to-face with friends and participating in important rituals of teenhood like sports events or graduation, have been abruptly taken away, replaced with unprecedented levels of social isolation, anxiety, and stress.

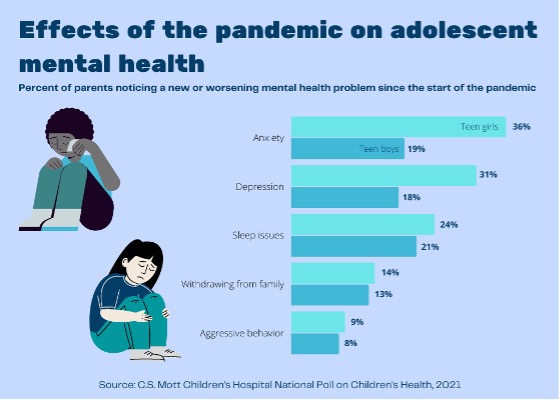

Since COVID-19 began its insidious erosion of our collective mental health, several recent analyses demonstrate an increase in teen symptoms of common mental health disorders like anxiety and depression. Youth demand for mental healthcare in a post-COVID-19 world has also soared, with the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reporting an increased proportion of mental health emergency room visits for children ages 5-17 after the pandemic began.

However, although COVID-19 certainly has exacerbated the crisis, worsening adolescent mental health is far from a new concern. Even before the pandemic, from 2005 to 2017, the rate of depression in children ages 12-17 increased over 50%. Suicide remains the second-leading cause of death for children ages 10-17, with the rate of suicide here in North Carolina almost doubling between 2008 and 2017. Despite increasing awareness of this concerning trend, less than half of children ages 12-17 who had experienced depressive episodes during this period received treatment, suggesting that there remain serious barriers in accessing appropriate care.

Across the country, many strategies to address adolescent mental health appropriately take a systemic approach, recognizing value in increasing investments in youth access to mental health care. For a local example, North Carolina Gov. Roy Cooper in February signed Senate Bill 36, which allocates $1.6 billion of federal funds to schools, in part to expand mental health services for students. Nationally, the Mental Health Services for Students Act, a $200 million competitive grant program to fund mental health services in schools, has passed the United States House of Representatives.

The importance of efforts like these in making mental health care more widely accessible and expansive cannot be overstated. However, we are remiss as a society to have a conversation about mental health without involving children’s most important resource — their parents and caregivers. Parents play a remarkably important role in helping their teens cope with stressors like the pandemic and are uniquely positioned to be the first to spot small changes in their teens’ behaviors that may be warning signs of mental health distress. As a front line resource for their children, parents are the true gatekeepers to adolescent mental health – an enormous task that many rightfully feel unprepared and under-resourced to handle.

Parenting advice and resources, which exist in droves for the newborn and toddler phases, fade away as children age, but the need for accurate and age-appropriate advice remains. Over 40% of parents find it difficult to distinguish between typical mood changes and signs of mental illness, and signs of mental illness in adolescents are often dismissed by parents as disobedience or misbehavior. Parents may also inadvertently exacerbate mental health issues, often unintentionally, by downplaying or invalidating their teens’ experiences, even if they are trying to help. While all parents can, and should, keep the lines of communication with their children open and create space for their teens to share struggles and concerns, holding these conversations and creating these environments isn’t easy.

When half of all chronic mental health issues have started by age 14, equipping parents with the tools to provide early detection and appropriate access to mental health care is just as important as expanding mental health resources for adolescents. In fact, the scarcity of resources for parents was the motivation for us to design and launch UNC Children’s Adolescent Mental Health Parenting Program for Child-Adult Relationship Enhancement (AMP-CARE) this year, where parents are already highlighting the need for similar grassroots programming. As one parent reflected at the conclusion of the program, “I feel like we were able to have a good conversation about [mental health] with our daughter, to make it not such a taboo subject, that she can come to us if she’s feeling depressed and down,” programs like AMP-CARE empower caregivers to tackle adolescent mental health, altering the trajectory of their teens’ lives in long-term and meaningful ways.

It is long past the time when we needed to blow open the conversation about adolescent mental health to include parents. The support that children receive from all avenues, caregivers included, forever shapes their abilities to become resilient and successful young adults. Now, more than ever, we must invest in a fully comprehensive approach to adolescent mental health, including community programming that gives parents the tools to recognize and act on early signs of mental health distress in their children, before a crisis happens.

References linked above in order (APA)

- Rogers, A. A., Ha, T., & Ockey, S. (2021). Adolescents’ Perceived Socio-Emotional Impact of COVID-19 and Implications for Mental Health: Results From a U.S.-Based Mixed-Methods Study. Journal of Adolescent Health, 68(1), 43–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.09.039

- C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital (March 15, 2021). Mott Poll Report: How the pandemic has impacted teen mental health. National Poll on Children’s Health. https://mottpoll.org/reports/how-pandemic-has-impacted-teen-mental-health

- Leeb, R.T., Bitsko, R.H., Radhakrishnan, L., Martinez, P., Njai, R., & Holland, K.M. (2020). Mental Health-Related Emergency Department Visits Among Children Aged <18 Years During the COVID-19 Pandemic – United States, January 1-October 17, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, 69, 1675-1680. http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6945a3

- Twenge, J. M., Cooper, A. B., Joiner, T. E., Duffy, M. E., & Binau, S. G. (2019). Age, period, and cohort trends in mood disorder indicators and suicide-related outcomes in a nationally representative dataset, 2005–2017. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 128(3), 185–199. https://doi.org/10.1037/abn0000410

- NC Child: The Voice for North Carolina’s Children (2019). North Carolina Child Health Report Card, 2019. https://ncchild.org/publications/child-health-report-card-2019/.

- C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital (November 18, 2019). Mott Poll Report: Recognizing youth depression at home and school. National Poll on Children’s Health. https://mottpoll.org/reports/recognizing-youth-depression-home-and-school

- NAMI (March 2021). Mental Health By the Numbers. National Alliance on Mental Illness. https://www.nami.org/mhstats